Top Stereotypes of African Americans Today

Widespread and Pervasive Stereotypes of African Americans

Stereotypes of African Americans grew as a natural consequence of both scientific racism and legal challenges to both their personhood and citizenship. In the 1857 Supreme Court case, Dred Scott v. John F.A. Sandford, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney dismissed the humanness of those of African descent. This legal precedent permitted the image of African Americans to be reduced to caricatures in popular culture.

Decades-old ephemera and current-day incarnations of African American stereotypes, including Mammy, Mandingo, Sapphire, Uncle Tom and watermelon, have been informed by the legal and social status of African Americans. Many of the stereotypes created during the height of the trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and were used to help commodify black bodies and justify the business of slavery. For instance, an enslaved person, forced under violence to work from sunrise to sunset, could hardly be described as lazy. Yet laziness, as well as characteristics of submissiveness, backwardness, lewdness, treachery, and dishonesty, historically became stereotypes assigned to African Americans.

Instead of focusing on stereotypes, which can be harmful and inaccurate, let’s explore some of the diverse realities and rich cultural contributions of African Americans in today’s world.

Here are some areas where African Americans are making significant contributions:

- Arts and Culture: From music and literature to visual arts and fashion, African Americans continue to shape and redefine cultural landscapes globally.

- Entrepreneurship and Business: Black-owned businesses are thriving in various sectors, contributing to economic growth and creating opportunities for others.

- Science and Technology: African American scientists and inventors are making groundbreaking discoveries and innovations in fields like medicine, engineering, and computer science.

- Academia and Education: Black scholars and educators are breaking barriers and inspiring future generations through their knowledge and dedication.

- Social Justice and Activism: African Americans remain at the forefront of movements fighting for equality, justice, and human rights for all.

These are just a few examples of the diverse and vibrant tapestry of African American experiences in the 21st century. By focusing on the positive contributions and acknowledging the complexities of their history and experiences, we can move beyond stereotypes and celebrate the true richness of African American culture and identity.

Remember, judging individuals based on stereotypes is unfair and inaccurate. Every person is unique and deserves to be treated with respect and understanding. Let’s celebrate the diversity and achievements of African Americans and work towards a more inclusive and equitable future for all.

BUT THEY EXIST !

The gallery was not found!

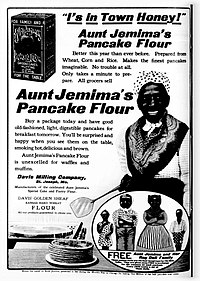

The Mammy stereotype developed as an offensive racial caricature constructed during slavery and popularized primarily through minstrel shows. Enslaved black women were highly skilled domestic works, working in the homes of white families and caretakers for their children. The trope painted a picture of a domestic worker who had undying loyalty to their slaveholders, as caregivers and counsel. This image ultimately sought to legitimize the institution of slavery. The Mammy stereotype gained increased popularity after the Civil War and into the 1900s. During this time her robust, grinning likeness was attached to mass-produced consumer goods from flour to motor oil. Considered a trusted figure in white imaginations, mammies represented contentment and served as nostalgia for whites concerned about racial equality.

The Pearl Milling Company’s incarnation of the smiling domestic, Aunt Jemima, became synonymous with the mammy stereotype. In 1899 the company hired real-life cook Nancy Green to portray the character at various state and world fairs. The stereotype of the overweight, self-sacrificing and dependent mammy figure would also grow alongside the American film industry through works including “Birth of a Nation” (1915), “Imitation of Life” (1934) and “Gone with the Wind” (1939).

Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom cartoon clip”Uncle Tom,” written by Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1852, featured the title character as a “large, broad-chested, powerfully made man … whose truly African features were characterized by an expression of grave and steady good sense, united with much kindliness and benevolence.” He forfeits his own chance at escaping bondage and loses his life to ensure the freedom of other slaves. The stereotype of Uncle Tom is innately submissive, obedient and in constant desire of white approval. The term became popular during the Great Migration when many Southern-born blacks moved to Northern cities like New York, Chicago and Detroit. With them, they brought codes of conduct expected in hostile Jim Crow environments. The stereotype was first publicly recorded during an address by Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association member Rev. George Alexander McGuire in 1919.

Sapphire

The Sapphire caricature, from the 1800s through the mid-1900s, popularly portrayed black women as sassy, emasculating and domineering. Unlike the Mammy figure, this trope depicted African American women as aggressive, loud, and angry – in direct violation of social norms. The Sapphire stereotype earned its name on the CBS television show “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” in association with the character Sapphire Stevens. Airing from 1951 to 1953 with an all-black cast, Sapphire Stevens was the wife to George “Kingfish” Stevens, a character depicted as ignorant and lazy – fueling Sapphire’s rage.

During the Jim Crow period, when blacks were often beaten, jailed, or killed for arguing with whites, these fictional characters would pretend-chastise whites, including men. Their sassiness was supposed to indicate their acceptance as members of the white family, and acceptance of that sassiness implied that slavery and segregation were not overly oppressive.

Watermelon

Man with Watermelon

Before it became a racist stereotype in the Jim Crow era, watermelon once symbolized self-sufficiency among African Americans. Following Emancipation, many Southern African Americans grew and sold watermelons, and it became a symbol of their freedom. Many Southern whites reacted to this self-sufficiency by turning the fruit into a symbol of poverty. Watermelon came to symbolize a feast for the “unclean, lazy and child-like.” To shame black watermelon merchants, popular ads and ephemera, including postcards pictured African Americans stealing, fighting over, or sitting in streets eating watermelon. Watermelons being eaten hand to mouth without utensils made it impossible to consume without making a mess, therefore branded a public nuisance.

Mandingo (The Black Buck)

Conjured by the minds of enslavers and auctioneers to promote the strength, breeding ability, and agility of muscular young black men, the Mandingo trope was born. While under the violence of enslavement, a physically powerful black man could be subdued and brutally forced into labor. Emancipation brought with it fears that these men would exact sexual revenge against white men through their daughters, as depicted in the film “Birth of a Nation” (1915). The reinforcement of the stereotype of the Mandingo as animalistic and brutish, gave legal authority to white mobs and militias who tortured and killed black men for the safety of the public.

Headlines of newspapers across the nation, beginning around the turn-of-the-century, document a frenzy of arrests, attempted lynchings and murders of “black brutes” accused of insulting or assaulting white women. Heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson epitomized the Mandingo or Black Brute of white imaginations in the flesh. Called a beast, a brute and a coon in print, Johnson’s relationships with white women took up as much newsprint as his fighting abilities. With his 1910 victory over James Jeffries, promoted as the “Great White Hope,” Johnson brought white fears to a head. The result was weeks of riotous mob violence across the nation that left thousands of African American communities and lives in ruin.

wikipedia

Stereotypes of African Americans are misleading beliefs about the culture of people with partial or total ancestry from any black racial groups of Africa whose ancestors resided in the United States since before 1865, largely connected to the racism and the discrimination to which African Americans are subjected. These beliefs date back to the slavery of black people during the colonial era and they have evolved within American society.

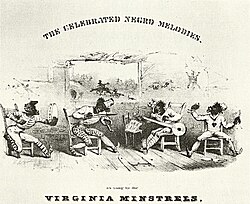

The first major displays of stereotypes of African Americans were minstrel shows. Beginning in the nineteenth century, they used White actors who were dressed in blackface and attire which was supposedly worn by African-Americans in order to lampoon and disparage blacks. Some nineteenth century stereotypes, such as the sambo, are now considered to be derogatory and racist. The “Mandingo” and “Jezebel” stereotypes portray African-Americans as hypersexual, contributing to their sexualization. The Mammy archetype depicts a motherly black woman who is dedicated to her role working for a white family, a stereotype which dates back to the origin of Southern plantations. African-Americans are frequently stereotyped as having an unusual appetite for fried chicken, watermelon, and grape drinks.

In the 1980s as well as in the following decades, emerging stereotypes of black men depicted them as being criminals and social degenerates, particularly as drug dealers, crack addicts, hobos, and subway muggers.[1] Jesse Jackson said the media portrays black people as less intelligent.[2] The magical Negro is a stock character who is depicted as having special insight or powers, and has been depicted (and criticized) in American cinema.[3] In recent history, black men are stereotyped as being deadbeat fathers.[4] African American men are also stereotyped as being dangerous criminals.[5] African Americans are frequently stereotyped as being hypersexual, athletic, uncivilized, uneducated and violent. Young urban African American men are frequently labelled “gangstas” or “players.”[6][7]

Stereotypes of black females include depictions which portray them as welfare queens or depictions which portray them as angry black women who are loud, aggressive, demanding, and rude.[8]

Laziness, submissiveness, backwardness, lewdness, treachery, and dishonesty are stereotypes historically assigned to African Americans.[9]

Historical stereotypes

Minstrel shows became a popular form of theater during the nineteenth century, which portrayed African Americans in stereotypical and often disparaging ways, some of the most common being that they are ignorant, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, joyous, and musical.[10] One of the most popular styles of minstrelsy was Blackface, where White performers burnt cork and later greasepaint or applied shoe polish to their skin with the objective of blackening it and exaggerating their lips, often wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes to give a mocking, racially prejudicial theatrical portrayal of African Americans.[11] This performance helped introduce the use of racial slurs for African Americans, including “darky” and “coon“.[12]

The best-known stock character is Jim Crow, among several others, featured in innumerable stories, minstrel shows, and early films with racially prejudicial portrayals and messaging about African Americans.

Jim Crow

The character Jim Crow was dressed in rags, battered hat, and torn shoes. The actor wore Blackface and impersonated a very nimble and irreverently witty black field hand.[13] The character’s popular song was “Turn about and wheel about, and do just so. And every time I turn about I Jump Jim Crow.”[14]

Sambo, Golliwog, and pickaninny

The character Sambo was a stereotype of black men who were considered very happy, usually laughing, lazy, irresponsible, or carefree.[12] The Sambo stereotype gained notoriety through the 1898 children’s book The Story of Little Black Sambo by Helen Bannerman. It told the story of a boy named Sambo who outwitted a group of hungry tigers. This depiction of black people was displayed prominently in films of the early 20th century. The original text suggested that Sambo lived in India, but that fact may have escaped many readers. The book has often been considered to be a slur against Africans.

The character found great popularity among other Western nations, with the Golliwog remaining popular well into the twentieth century.[clarification needed] The derived Commonwealth English epithet “wog” is applied more often to people from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian subcontinent than to African-Americans, but “Golly dolls” still in production mostly retain the look of the stereotypical blackface minstrel.[15]

The term pickaninny, reserved for children, has a similarly broadened pattern of use in popular American theater and media. It originated from the Spanish term “pequeño niño” and the Portuguese term “pequenino” to describe small child in general, but it was applied especially to African-American children in the United States and later to Australian Aboriginal children.[16]

Black children as alligator bait

A variant of the pickaninny stereotype depicted black children being used as bait to hunt alligators.[17] Although scattered references to the supposed practice appeared in early 20th-century newspapers, there is no credible evidence that the stereotype reflected an actual historical practice.

Mammy

The Mammy archetype describes African-American women household slaves who served as nannies giving maternal care to the white children of the family, who received an unusual degree of trust and affection from their enslavers. Early accounts of the Mammy archetype come from memoirs and diaries that emerged after the American Civil War, idealizing the role of the dominant female house slave: a woman completely dedicated to the white family, especially the children, and given complete charge of domestic management. She was a friend and advisor.[18]

Mandingo

The Mandingo is a stereotype of a sexually insatiable black man with a large penis, invented by white slave owners to advance the idea that Black people were not civilized but rather “animalistic” by nature.[19] The supposedly inherent physical strength, agility, and breeding abilities of Black men were lauded by white enslavers and auctioneers in order to promote the slaves they sold.[9] Since then, the Mandingo stereotype has been used to socially and legally justify spinning instances of interracial affairs between Black men and white women into tales of uncontrollable and largely one-sided lust. This stereotype has also sometimes been conflated with the ‘Black brute’ or ‘Black buck’ stereotype, painting the picture of an ‘untameable’ Black man with voracious and violent sexual urges.[20]

The term ‘Mandingo’ is a corrupted word for the Mandinka peoples of West Africa, presently populating Mali, Guinea, and the Gambia. One of the earliest usages found dates back to the 20th century with the publication of Mandingo, a 1957 historical erotica. The novel was part of a larger series which presented, in graphic and erotic detail, various instances of interracial lust, promiscuity, nymphomania, and other sexual acts on a fictional slave-breeding plantation.[21] In conjunction with the film Birth of a Nation (1915), white American media formed the stereotype of the Black man as an untamed beast who aimed to enact violence and revenge against the white man through the sexual domination of the white woman.[9]

Sapphire

The Sapphire stereotype defines Black women as argumentative, overbearing, and emasculating in their relationships with men, particularly Black men. She is usually shown to be controlling and nagging, and her role is often to demean and belittle the Black man for his flaws. This portrayal of a verbally and physically abusive woman for Black women goes against common norms of traditional femininity, which require women to be submissive and non-threatening.[22][23] During the era of slavery, white slave owners inflated the image of an enslaved Black woman raising her voice at her male counterparts, which was often necessary in day-to-day work. This was used to contrast the loud and “uncivilized” Black woman against the white woman, who was considered more respectable, quiet, and morally behaved.[24]

The popularization of the Sapphire stereotype dates back to the successful 1928-1960 radio show Amos ‘n’ Andy, which was written and voiced by white actors. The Black female character Sapphire Stevens was the wife of George “Kingfish” Stevens, a Black man depicted as lazy and ignorant. These traits were often a trigger for Sapphire’s extreme rage and violence. Sapphire was positioned as overly confrontational and emasculating of her husband, and the show’s popularity turned her character into a stock caricature and stereotype.[9][25]

This stereotype has also developed into the trope of the ‘Angry Black Woman‘, overall portraying Black American women as rude, loud, malicious, stubborn, and overbearing in all situations, not only in their relationships.

Jezebel

The Jezebel is a stereotype of a hypersexual, seductive, and sexually voracious Black woman. Her value in society or the relative media is based almost purely on her sexuality and her body.[26]

The roots of the Jezebel stereotype emerged during the era of chattel slavery in the United States. White slave owners exercised control over enslaved Black women’s sexuality and fertility, as their worth on the auction block was determined by their childbearing ability, ie. their ability to produce more slaves.[27] The sexual objectification of Black women redefined their bodies as “sites of wild, unrestrained sexuality”,[28] insatiably eager to engage in sexual activity and become pregnant. In reality, enslaved Black women were reduced to little more than breeding stock, frequently coerced and sexually assaulted by white men.[29]

Post-emancipation, the sexualization of Black women has remained rampant in Western society. Modern-day Jezebels are pervasive in popular music culture; Black women more often appear in music videos with provocative clothing and hypersexual behaviour compared to other races, including white women.[26] The Jezebel stereotype has also contributed to the adultification and sexualization of Black adolescent girls.[30]

Tragic mulatta

A stereotype that was popular in early Hollywood, the “tragic mulatta,” served as a cautionary tale for black people. She was usually depicted as a sexually attractive, light-skinned woman who was of African descent but could pass for Caucasian.[31] The stereotype portrayed light-skinned women as obsessed with getting ahead, their ultimate goal being marriage to a white, middle-class man. The only route to redemption would be for her to accept her “blackness.”

Uncle Tom

The Uncle Tom stereotype represents a black man who is simple-minded and compliant but most essentially interested in the welfare of whites over that of other blacks. It derives from the title character of the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and is synonymous with black male slaves who informed on other black slaves’ activities to their white master, often referred to as a “house Negro“, particularly for planned escapes.[32] It is the male version of the similar stereotype Aunt Jemima.

Black brute, Black Buck

Black brutes or black bucks are stereotypes for black men, who are generally depicted as being highly prone to behavior that is violent and inhuman. They are portrayed to be hideous, terrifying black male predators who target helpless victims, especially white women.[33] In the post-Reconstruction United States, ‘black buck’ was a racial slur used to describe black men who refused to bend to the law of white authority and were seen as irredeemably violent, rude, and lecherous.[34]

In art

From the Colonial Era to the American Revolution, ideas about African Americans were variously used in propaganda either for or against slavery. Paintings like John Singleton Copley‘s Watson and the Shark (1778) and Samuel Jennings’s Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences (1792) are early examples of the debate under way at that time as to the role of black people in America. Watson represents an historical event, but Liberty is indicative of abolitionist sentiments expressed in Philadelphia’s post-revolutionary intellectual community. Nevertheless, Jennings’ painting represents African Americans in a stereotypical role as passive, submissive beneficiaries of not only slavery’s abolition but also knowledge, which liberty had graciously bestowed upon them.

As another stereotypical caricature “performed by white men disguised in facial paint, minstrelsy relegated black people to sharply defined dehumanizing roles.” With the success of T. D. Rice and Daniel Emmet, the label of “blacks as buffoons” was created.[35] One of the earliest versions of the “black as buffoon” can be seen in John Lewis Krimmel‘s Quilting Frolic. The violinist in the 1813 painting, with his tattered and patched clothing, along with a bottle protruding from his coat pocket, appears to be an early model for Rice’s Jim Crow character. Krimmel’s representation of a “[s]habbily dressed” fiddler and serving girl with “toothy smile” and “oversized red lips” marks him as “…one of the first American artists to use physiognomical distortions as a basic element in the depiction of African Americans.”[35]

Contemporary stereotypes

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014)

|

Crack addicts and drug dealers

Scholars agree that news-media stereotypes of people of color are pervasive.[36][37][38][39][40][41] African Americans were more likely to appear as perpetrators in drug and violent crime stories in the network news.[42]

In the 1980s and the 1990s, stereotypes of black men shifted and the primary and common images were of drug dealers, crack victims, the underclass and impoverished, the homeless, and subway muggers.[1] Similarly, Douglas (1995), who looked at O. J. Simpson, Louis Farrakhan, and the Million Man March, found that the media placed African-American men on a spectrum of good versus evil.

Watermelon and fried chicken

There are commonly held stereotypes that African Americans have an unorthodox appetite for watermelons and love fried chicken. Race and folklore professor Claire Schmidt attributes the latter both to its popularity in Southern cuisine and to a scene from the film Birth of a Nation in which a rowdy African-American man is seen eating fried chicken in a legislative hall.[43]

Welfare queen

The welfare queen stereotype depicts an African-American woman who defrauds the public welfare system to support herself, having its roots in both race and gender. This stereotype negatively portrays black women as scheming and lazy, ignoring the genuine economic hardships which black women, especially mothers, disproportionately face.[44]

Magical Negro

The magical Negro (or mystical Negro) is a stock character who appears in a variety of fiction and uses special insight or powers to help the white protagonist. The Magical Negro is a subtype of the more generic numinous Negro, a term coined by Richard Brookhiser in National Review.[45] The latter term refers to clumsy depictions of saintly, respected or heroic black protagonists or mentors in US entertainment.[45]

Angry black woman

In the 21st century, the “angry black woman” is depicted as loud, aggressive, demanding, uncivilized, and physically threatening, as well as lower-middle-class and materialistic.[8] She will not stay in what is perceived as her “proper” place.[46]

Controlling image

Controlling images are stereotypes that are used against a marginalized group to portray social injustice as natural, normal, and inevitable.[47] By erasing their individuality, controlling images silence black women and make them invisible in society.[8] The misleading controlling image present is that white women are the standard for everything, even oppression.[46]

Education

Studies show that scholarship has been dominated by white men and women.[48] Being a recognized academic includes social activism as well as scholarship. That is a difficult position to hold since white counterparts dominate the activist and social work realms of scholarship.[48] It is notably difficult for a black woman to receive the resources needed to complete her research and to write the texts that she desires.[48] That, in part, is due to the silencing effect of the angry black woman stereotype. Black women are skeptical of raising issues, also seen as complaining, within professional settings because of their fear of being judged.[8]

Mental and emotional consequences

Due to the angry black woman stereotype, black women tend to become desensitized about their own feelings to avoid judgment.[49] They often feel that they must show no emotion outside of their comfortable spaces. That results in the accumulation of these feelings of hurt and can be projected on loved ones as anger.[49] Once seen as angry, black women are always seen in that light and so have their opinions, aspirations, and values dismissed.[49] The repression of those feelings can also result in serious mental health issues, which creates a complex with the strong black woman. As a common problem within the black community, black women seldom seek help for their mental health challenges.[50]

Interracial relationships

Oftentimes, black women’s opinions are not heard in studies that examine interracial relationships.[51] Black women are often assumed to be just naturally angry. However, the implications of black women’s opinions are not explored within the context of race and history. According to Erica Child’s study, black women are most opposed to interracial relationships.[51]

Since the 1600s, interracial sexuality has represented unfortunate sentiments for black women.[51] Black men who were engaged with white women were severely punished.[51] However, white men who exploited black women were never reprimanded. In fact, it was more economically favorable for a black woman to birth a white man’s child because slave labor would be increased by the one-drop rule. It was taboo for a white woman to have a black man’s child, as it was seen as race tainting.[51] In contemporary times, interracial relationships can sometimes represent rejection for black women. The probability of finding a “good” black man was low because of the prevalence of homicide, drugs, incarceration, and interracial relationships, making the task for black women more difficult.[51]

As concluded from the study, interracial dating compromises black love.[51] It was often that participants expressed their opinions that black love is important and represents more than the aesthetic since it is about black solidarity.[51] “Angry” black women believe that if whites will never understand black people and they still regard black people as inferior, interracial relationships will never be worthwhile.[51] The study shows that most of the participants think that black women who have interracial relationships will not betray or disassociate with the black community, but black men who date interracially are seen as taking away from the black community to advance the white patriarchy.[51]

“Black bitch”

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2016)

|

The “black bitch” is a contemporary manifestation of the Jezebel stereotype. Characters termed “bad black girls,” “black whores,” and “black bitches” are archetypes of many blaxploitation films produced by the Hollywood establishment.[52]

Strong black woman

The “strong black woman” stereotype is a discourse through that primarily black middle-class women in the black Baptist Church instruct working-class black women on morality, self-help, and economic empowerment and assimilative values in the bigger interest of racial uplift and pride (Higginbotham, 1993). In this narrative, the woman documents middle-class women attempting to push back against dominant racist narratives of black women being immoral, promiscuous, unclean, lazy and mannerless by engaging in public outreach campaigns that include literature that warns against brightly colored clothing, gum chewing, loud talking, and unclean homes, among other directives.[53] That discourse is harmful, dehumanizing, and silencing.

The “strong black woman” narrative is a controlling image that perpetuates the idea it is acceptable to mistreat black women because they are strong and so can handle it. This narrative can also act as a silencing method. When black women are struggling to be heard because they go through things in life like everyone else, they are silenced and reminded that they are strong, instead of actions being taken toward alleviating their problems.[53]

Independent black woman

The “independent black woman” is the depiction of a narcissistic, overachieving, financially successful woman who emasculates black males in her life.[54]

Black American princess

Athleticism

Blacks are stereotyped as being more athletic and superior at sports than other races. Even though they make up only 12.4 percent of the US population, 75% of NBA players[55] and 65% of NFL players are black.[56] African-American college athletes may be seen as getting into college solely on their athletic ability, not their intellectual and academic merit.[57]

Black athletic superiority is a theory that says blacks possess traits that are acquired through genetic and/or environmental factors that permits them to excel over other races in athletic competition. Whites are more likely to hold such views, but some blacks and other racial affiliations do as well.[58]

Several other authors have said that sports coverage that highlights “natural black athleticism” has the effect of suggesting white superiority in other areas, such as intelligence.[59] The stereotype suggests that African Americans are incapable of competing in “white sports” such as ice hockey[60] and swimming.[61]

Intelligence

Following the stereotypical character archetypes, African Americans have falsely and frequently been thought of and referred to as having little intelligence compared to other racial groups, particularly white people.[62] This has factored into African Americans being denied opportunities in employment. Even after slavery ended, the intellectual capacity of black people was still frequently questioned.

Stephen Jay Gould‘s book The Mismeasure of Man (1981) demonstrated how early 20th-century biases among scientists and researchers affected their purportedly objective scientific studies, data gathering, and conclusions which they drew about the absolute and relative intelligence of different groups and of gender and intelligence.[citatio